The Immense Pressure That Comes Being a First Gen Immigrant

September 30, 2021

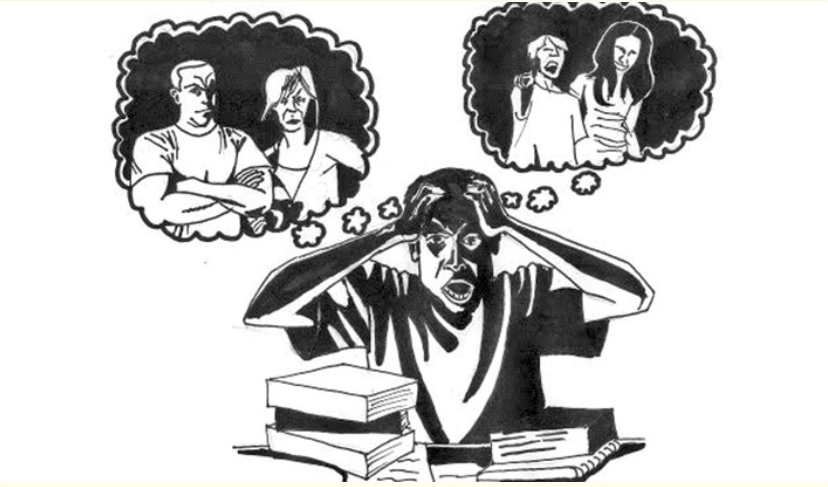

Jafet Pichardo has always strived to be at her academic best, but this motivation comes at a cost– as a first generation immigrant student, her drive to succeed stems from parental pressure. She can recall moments since her childhood, when her parents referred to mental health as not being a priority or that it was a minor problem. Now, as a sophomore in the International Baccalaureate Program (IB), this statement and mindset has heavily influenced her realization that her parents don’t take into account her mental health and that academic success will always triumph.

“People perceive me as really smart, like on paper it seems like I’m really intelligent and good in school,” Pichardo said. “The reason I’m good at school is because I’m scared of failing.”

Pichardo is not the only one feeling this massive pressure from her immigrant parents, as many first-generation immigrant students feel the same way. According to students in similar households, it is common for immigrant parents to prioritize their child’s education over mental health, because immigrant parents have worked hard, placing an expectation to succeed.

Students under foreign households have immigrant families who come from countries that do not offer the same accessibility to education like the United States. According to a study by Pew Research, Mexico is considered the top origin country for the US immigrant population with 11.2 million immigrants living in the US in 2018. Mexico ranks last within education, leaving most of the children with literacy, math, and science skills that fail to meet most of the basic standards of education (as founded by 35 Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)) Mexico and Mexican immigrants are an example of how education is very poor within their home country, and that is why they seek opportunities within the US.

“I think my dad made it to like fifth grade level and my mom made it halfway to junior year of high school,” Pichardo said.

A perspective that first generation students live with, is that their parents had a less likely chance of finishing school and getting to the education level they want, which is why it is common for them to force their dreams and aspirations on their children. Immigrant parents most often believe that college signifies success and that it will make or break if someone will have a good career.

“From the immigrant mindset, college is like the ‘‘Hail Mary’’ of success,” senior Trishya Singian said.

Parents often are entirely focused on their childrens’ futures and success that they overlook the mental health aspects and the signs that their childrens’ health is deteriorating under this reinforcement to always perform well.

“[My parents] both suffer from mental health, but they don’t understand it.” Pichardo said. “They think it’s something that shouldn’t be talked about. It’s not something normal because if it isn’t physical pain, then it’s not pain.”

Mental illness affects about 1 out of 5 U.S. adults according to a study conducted in 2019 by the National Institute of Mental Health. Mental illnesses and disorders include depression, anxiety, personality disorders, etc. Around 6.7% of the American population had depression in 2020. Depression and other mental illnesses can lead to suicide and an unhappy life for the individual. Having a deteriorating mental health impacts personal relationships and everyday routines, which can spin a person out of order and lead them down to a demoralizing path. Additionally, a decaying mental health will affect one’s personal self worth. It poses the question of whether or not academic success is really more important than taking care of one’s mental health.

“Parental pressure makes me want to do good in school, but at the same time, it makes me feel like I’m not living my life,” Pichardo said. “Like they’re living through me and want me to do good so that they can feel happiness within myself because they want me to succeed.”

Another viewpoint that first generation students share, is their parents comparing their grades to others’ grades, extracurricular activities, and achievements.

“When we were younger it was very prevalent,” Singian said. “They would ask me like why am I not like my sister and it was other stuff like that too. It would make me feel like I’m not enough.”

As being children of immigrants, they feel both the parental and internal pressure to be the best. This feeling can sometimes consume them entirely to the point they develop mental conditions.

“[The pressure] has definitely taken a mental toll on me,” Singian said. “I did see a psychiatrist in the past week about my depression and anxiety, it also runs within my sisters and I, who are first generation.”

Immigrant parents and older generations in general rarely sought out help for their mental health and this ongoing mindset has been passed down to present day first generation children. According to an American Psychological Association survey, 37% of present day teens reported that they reached out for treatment for their mental health issues. This statistic contrasts with 26% of Gen Xers (1965-1980), 22% of baby boomers (1946-1964), and 15% of older adults reported. With this generational decline, it shows that it was peculiar for individuals to seek mental help, meaning that it is quite possible that immigrant parents that were unable to seek help for themselves, believe their children do not need help.

“The other day I was crying at my kitchen table because I could not understand something,” Pichardo said. “[My parents] say things will get better, but then leave and don’t care about how I am crying. As long as they see that I get it done.”